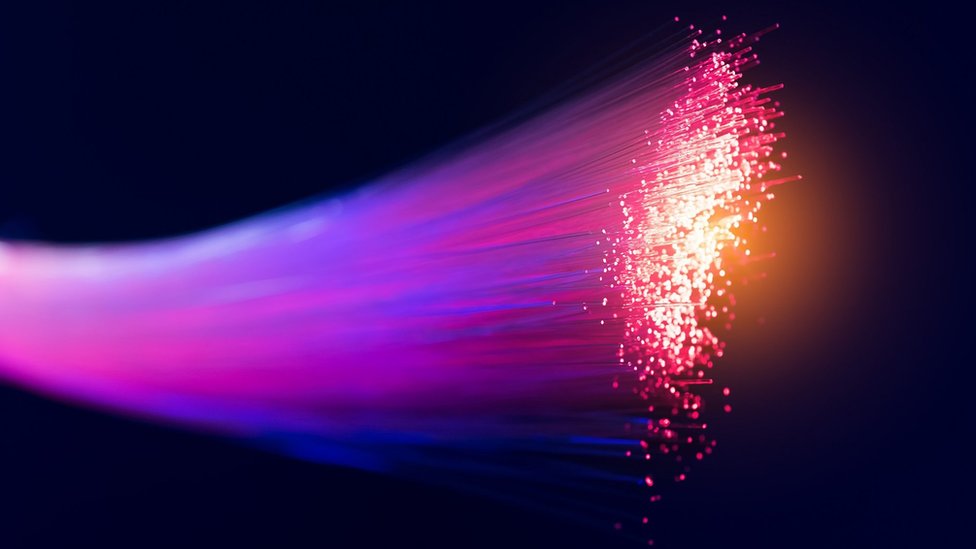

Andreas Fichtner strips a cable of its protective sheath, exposing a glass core thinner than a hair — a fragile, 4-kilometer-long fiber that’s about to be fused to another. It’s a fiddly task better suited to a lab, but Fichtner and his colleague Sara Klaasen are doing it atop a windy, frigid ice sheet.

After a day’s labor, they have spliced together three segments, creating a 12.5-kilometer-long cable. It will stay buried in the snow and will snoop on the activity of Grímsvötn, a dangerous, glacier-covered, Icelandic volcano.

Sitting in a hut on the ice later on, Fichtner’s team watches as seismic murmurs from the volcano beneath them flash across a computer screen: earthquakes too small to be felt but readily picked up by the optical fiber. “We could see them right under underneath our feet,” he says. “You’re sitting there and feeling the heartbeat of the volcano.”